Nagarjuna and a cup of coffee

(for a primer on the doctrine of emptiness read my last blog post here)

"we do not explain

without accepting conventions" —Nargajuna, Rebuttal of Objections

Nargajunas teachings emphasize the empty nature of phenomena throughout his works. Much in the same way that dreams arise from no source and have no actual content yet are experienced as reality, the phenomenal world is taught to be an illusion whose true nature is dependent origination. This means that a coffee cup cannot be viewed apart from the endless chain of conditions that brought it into existence. The clay it was shaped from was dug up from the ground that was once an ancient seabed made of sediment of particles of even more ancient volcanoes. The hands that shaped it arrived at that moment from an infinite series of beings who survived since the beginning of life on earth, which was preceded by the 4 billion years of cosmic evolution that created atmospheric conditions on earth that allow water molecules to survive. All apparent phenomena are an atemporal web of (illusory) existence and cannot be categorically isolated from the causes that created them. And if everything is one thing, there is no duality, and everything is also nothing; thus it is beyond our relative conceptions of existing, or not existing.

Despite this, we still have the experience of holding a coffee cup. This is the same experience we might have holding a coffee cup in a dream, in fact there ultimately is no difference between the two. Still, we have words to describe them both. Words are also a thread of dependent origination, and equally as unreal as any other phenomena. When explaining the world in any capacity, it is necessary to describe things in relative, conventional terms, because that is one of the few ways we have to transmit the answers of how to see beyond the illusion. It is also possible to realize this truth directly with no instruction or need for relative truths; we use the training wheels of explanation to help arrive there. This is why phenomena is taught to be empty, it has the appearance to us of existing independently when in fact there is no such thing.

The doctrine of emptiness

The Prajnaparamita sutras were a series of Buddhist philosophical texts written around 100 C.E., centering around the concept of sunyata. This word has been translated as emptiness, voidness, spaciousness, and lacking an intrinsic nature. This philosophy was not initially a departure from earlier Buddhist doctrine, but as later thinkers gave their commentaries and interpretations a new school began to emerge; the Madhyamaka.

Early Buddhist sutras describe a dualist philosophy: both relative and ultimate truth exist. Nagarjuna was a Madhyamaka philosopher who systematically argued for why this is a logically incoherent position, disproven by its own internal reasoning. Instead, he advocated for a philosophy based upon the Prajñaparamita doctrine of emptiness; which states that feeling, thought, consciousness, and form, are all equally unmanifest. While earlier Buddhist philosophers (and later Yogacara philosophers) held positions asserting some of these qualities to hold truth and others to be illusory, Madhyamaka doctrine held that all were equally illusory, non-existent, and beyond conceptualization. As Nargajuna puts it “nowhere does anything ever arise”. Siderits describes the same thing in a more easily digestible way: “there can be no ultimately true account of the nature of reality”.

Nargajuna uses many logical arguments to prove that this stance is the only defensible one. He asserts that anything that is compounded lacks intrinsic nature, and proves all things, including consciousness, to be compounded and interdependent. He also uses motion to prove that there is no ground for phenomena to stand upon that would allow it to exist. I think Nargajunas most important assertion is that even the doctrine of emptiness is something that needs to ultimately be abandoned. In the MMK he states: “Emptiness is taught by the conquerors as the expedient to get rid of all [metaphysical] views. But those for whom emptiness is a [metaphysical] view, they have been called incurable”. Emptiness is a tool that allows us to release the wrong views that shape our philosophies, but it needs to be left behind as well to arrive at the place it describes.

In my opinion the doctrine of emptiness is best described through poetry and paradox, the Prajnaparamita sutras that set off this movement are a shining example of this. Emptiness is a concept that can only be articulated indirectly, through showing what it is not. All phenomena are fever dreams we perceive to be reality, the catch being that there is no dreamer. Emptiness is the pregnant void from which all phenomena manifest and return to. By accepting this philosophy, and then abandoning it altogether, emptiness is experienced even though it cannot be found.

Enter the Mahāyāna

After spending the past month exploring early Buddhist philosophy we’ve [finally] entered the second turning of the wheel. Mahayana Buddhism was a new branch of Buddhist thought that emerged in the first century C.E., about 500 years after the time of the historical Buddha. Mahayana literally translates as great vehicle, as the proponents of this school called this framework a more direct and purified form of what the Buddha taught. An important point early Buddhism makes is that a Buddha will teach according to the level of understanding of his audience. The Mahayana sutras take this claim literally, and say that in the 20 generations since that time, we’ve learned some shit and have a greater capacity for understanding. The crux of this is that Mahayana Buddhism expanded the definition of emptiness to encompass all phenomena, instead of just persons, and with this the ultimate goal of practice shifted to the liberation of all sentient beings (the bodhisattva ideal) instead of the expressed goal of the early Buddhist arhat, which was to transcend suffering.

from my teacher:~~ As these texts make clear, Mahāyāna Buddhists often consider their approach superior to other forms of Buddhism. In particular, Mahāyāna Buddhism often says that its emphasis on achieving enlightenment for the benefit of others makes it superior to other forms of Buddhism (sometimes referred to pejoratively as Hīnayāna, or “Lesser Vehicle” Buddhism) which only focus on achieving enlightenment for oneself. But in practice, both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna forms of Buddhism cultivate and practice many of the same things: morality, wisdom, and meditation. If you just look at what Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna practitioners actually do, it might be hard to tell them apart. The difference, then, is one of intention rather than actual practice.~~

PROMPT

How important do you think this difference is, really? Is the difference of intention really that big a deal? Remember that Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna Buddhism share many of the same practices.

༶

In any update, there will necessarily be differences from the original. In the Mahāyāna sutras, written 500 years after the time of the Buddha, the logic of emptiness was extended to apply to all phenomena instead of just persons, and the goal of liberation was shifted from ending one’s own suffering to ending that of all sentient beings. In both cases, the locus of the path was shifted from the self to the collective. Does this mean early Buddhism was a selfish philosophy and the Mahāyāna altruistic? That is not what I perceive in reading texts from both camps. I see an evolution in rational and linguistic capacities, but a core philosophy that remains the same.

We can think of this shift as a move up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs— While premodern times were more focused on survival, the improvement of general conditions allowed for a more nuanced collective worldview to unfold. Additionally, early Buddhism was limited to using pre-existing non-Buddhist language to define itself, while Mahayana sutras had the luxury of 20 generations of Buddhist discourse to work with. Early Buddhism used Annatā (literally no-self) to negate the pre-existing agreed-upon reality of the atman. Mahāyāna sutras had the advantage of this ground already being tread and could instead expand the concept and swim in the vast spaciousness of Sunyātā (void-ness), the emptiness of all phenomena. The Arhat emerged from a worldview occupied with the self due to survival needs, while the Bodhisattva ideal came at a time when language and material conditions allowed a more expansive sense of selfhood to take place.

While both schools describe the same core philosophy, the evolution in language allowed for an experiential shift in practice. While there may not be any practical difference between the Arhat and the Bodhisattva, the title gives each its own respective texture. Much like with foods, some people may perceive that difference as unimportant while to others it may feel monumental. I must admit I personally prefer the language of the latter. While I found working through the texts of early Buddhism to be very rich and informative, I couldn’t help but feel boxed in by the structure being so self-oriented. It's no fault of early Buddhism, that is just the language they had available at the time. I find the Mahayana sutras to be more conducive to the goal of liberation, as I find the collective focus to be a quicker tap into the experiential quality of liberation. In the Bodhisattva ideal, a space was created in which “the sudden lightning glares and all is clearly shown” as Shantideva states. While this is also possible in an early Buddhist framework, it feels to me that there is more sifting through the reeds required to get there. If expediency in liberation is our goal, I find the Mahāyāna sutras to be a better vehicle for arrival.

༶

Karma pt.2: take it or leave it

[Pt. 1 on karma can be found here]

“Some modern Buddhists don't like the idea of karma, and want to create a Buddhism without it. They believe that belief in karma is a holdover from overtly religious forms of Buddhism that is unnecessary in modern forms of the Buddhist tradition.”

PROMPT

How do you feel about this? How necessary is karma to Buddhist thought?

It is hard for me to conceive of a Buddhist outlook that does not include a belief in karma. At the same time, I think there are many aspects of Buddhist thought that could help alleviate suffering for modern agnostic or atheist people (or even practicing other religions), that could be transmitted without them needing to agree with the entire worldview. It seems to me that a lot of good would be necessarily lost in this process, but I think the outcome is overall positive— better to have bits and pieces of Buddhist philosophy to inform one's actions than none at all.

For me personally, karma is an empirical reality. I see no difference between the Buddha’s conception of karma and Newton’s third law of thermodynamics— For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. It doesn’t need to happen immediately and visibly for that to hold true. When paired with the concept of interdependence, it makes sense that those karmic repercussions would be spread out through spacetime. To deny that truth because it appears too mystical strikes me as a great loss, but I think the Buddhist philosophy of practicing mindfulness and non-attachment to lessen suffering can still hold without needing to ‘believe’ in karma. That viewpoint strikes me as more ignorant of observable facts than acceptance of karma as a reality, but that is shaped by my own lived experience of these truths. To argue that karma is at odds with a scientific view makes no sense to me, as I think every physics experiment is a lesson in karma.

At the same time, I think there exists the potential that one can be a good Buddhist without adhering any doctrine at all. I don’t think any belief system holds a monopoly on acceptance of impermanence and the experience of interconnection, and I think any person could come to those conclusions from their own journey and personal metaphysics without ever encountering Buddhist philosophy. While having a rational defensible Buddhist metaphysics was important for establishing legitimacy, I think the core of the teachings speaks to a state and experience far beyond the constraints of worldly explanation. I think the truth that leads to liberation is self-evident and universally accessible, but living in a time where we are indoctrinated with values so antithetical to that state, it takes most people a great amount of logical explanation and rationalization to get there. This is why I think the Buddha's teachings on karma are important and helpful, it is a piece that does a great amount of deprogramming the individualistic views that keep us trapped in a cycle of suffering. But ultimately, I think the core of the Buddha's teachings speak to the fact that liberation is beyond language and doctrine, and is freely available to anyone, anywhere, anytime.

Karma

This week the topic was karma. I see it as deeply connected to the doctrine of dependent origination so I explained it that way. Technical explanation in this post, opinions to follow in part 2~~

༶

“by what path will you lead him,

The trackless buddha of infinite range?” — The Dhammapada

I would like to explore the definition of karma through the lens of dependent origination. This philosophy is unique to Buddhism, and one of the major points of departure from the dominant philosophies at the time of the Buddha. Principally, the view at that time was that there is an Atman, or personal soul, that moves through reincarnations, and the actions it takes determines the quality of the rebirth it takes. The doctrine of dependent origination stands in direct contrast to this philosophy, as its basic unit of operation is the web of causality itself, not a singular entity thought to be a soul. Dependent origination forces us to look at ourselves and the world around us not as solid distinct entities, but instead as fluid processes that are always in motion and always changing. A key part of this philosophy is the interdependence of all phenomena. Things can only exist in context and relation to everything that surrounds them. This also applies to people, we exist contingent upon the matter that we are made from, the coming together of our parents, the community that supports us, and the resources we continually depend on for survival. Any action one can take is predicated on the endless forces that led to the creation of that urge in that moment, and the results of that action will cascade through space and time in the web of interconnected phenomena.

So how does this relate to the Buddhist view on karma? When we take dependent origination as our base and consider how cause and effect might look in such a system, we can see that we are dealing with something far more subtle and complex than a boomerang coming back when you throw it. Karma is the entire pulsing web of action and reaction, rippling between every person, place, and thing. An action taken may bear fruit for oneself, someone else, or no one; 2 minutes later, in a few lifetimes, or never. The connective tissue that is interdependence is mysterious in its operations, by nature of the sheer complexity of the mechanics. This is why the Buddha emphasized the value of practical advice as opposed to metaphysical pondering; how karma works does not matter as much as how its function impacts one's pursuit of liberation. This also allows for a spaciousness in his metaphysics, where one doesn’t have to look over one's shoulder to make sure not to step on any cracks out of fear of karmic repercussions, as there is so much fluidity in the web that it is unknown how or when karmic results might manifest. As such, the only thing that matters is doing one's best to have awareness of the inner experience so that reactions and emotions can be experienced with more clarity, and acted upon in ways that bring about the least suffering.

The value of virtuous behavior becomes self-evident when relating through the lens of dependent origination. We can see that taking good, positive action will lead to positive or neutral results for oneself or someone else somewhere in the great web of interdependence, and taking harmful action will do the opposite. Once we realize that we are connected to everything, the desire to hurt or harm begins to dissolve, as it becomes clear that any action taken against someone else will only end up harming ourselves, and generate more suffering for all parties. In the Buddha's teachings we are led to see karma as the connective tissue that binds the phenomenal world together, and we participate in it with every breath we take. The question then becomes how best to act to benefit the interdependent whole, instead of how to better ones own experience, as the latter becomes subsumed by the former.

༶

no-self pt. 2: And what about it?

Part 2 of this assignment was to respond with our own opinion on the doctrine of no-self. I hope this can help illuminate what it looks like on the ground to put this kind of philosophy into practice.

༶

I feel very comfortable with the notion of not having a self. The Buddhist doctrine of no-self has always resonated with me and makes sense in my mind; I find the philosophical arguments to be sound. I enjoy the experience of having a self in the conventionally true sense, I do not experience a lack of ultimate selfhood as being at odds with this. Both co-exist on their different planes of truth. I think it's important to remember the Buddha’s emphasis on his philosophy being the “middle way”. Despite the focus on the self as being not ultimately real, this doesn’t mean that we reject the conventional concept of a self. That would lead to asceticism and rejection of the body, a viewpoint that this philosophy was expressly countering. I see the philosophy of no-self as both embracing the existence of the conventional self and ultimate self at the same time, appreciating material existence for what it is; the interplay of phenomena. Knowing this, one can tread a little more lightly and loosen the grip on material attachments, and from that experience more peace and less suffering.

I had a conversation with a friend recently who was asking what Buddhists think about the feeling of passion. My response was that Buddhists think a feeling like passion is just as valuable or real as any other emotion, not any more desirable or undesirable than fear or indifference. I think it could be easy to read these texts and fall into the trap of thinking passion as deceptive and to be rejected, as it can lead one deeper into clinging to the material world and reify the conventional self. I don’t think that is an accurate view. When I experience great joy and passion, eating a piece of chocolate cake for example, I don’t reject the feeling moving through me. Instead, I look at it for what it is, a play of phenomena like a cloud in the sky. I take a step back and allow the feeling to happen without attaching my ego and sense of self to it, I enjoy it for what it is without taking it so seriously as being ultimately real. The beauty of this is when the cake is done and the feeling ends, I don’t feel as great of a sense of loss, instead it's just a different type of cloud moving through my mind.

This is not to say I have perfect detachment, nor am I necessarily aiming for that at this moment. I am comfortable both appreciating what materiality has to offer while knowing it isn't ultimately ‘real’. I felt more drive to reach ‘enlightenment’ when I was newer to this material. The longer I have spent with it, the more comfortable I feel with just being where I'm at, not believing I have to be the Dalai Lama to find peace. I feel that this is one of the great paradoxes of Buddhism, the longer I spend with it, the less of a need I feel to break the cycle of rebirth. At first the concept of no-self seems like it requires a radical letting go of one's identity into nothingness, never to be found again. In reality it seems to play out as a greater and greater comfort and acceptance with being who I am, as there isn’t so much clinging getting in the way of the simple act of being.

༶

ultimate truth/No-self

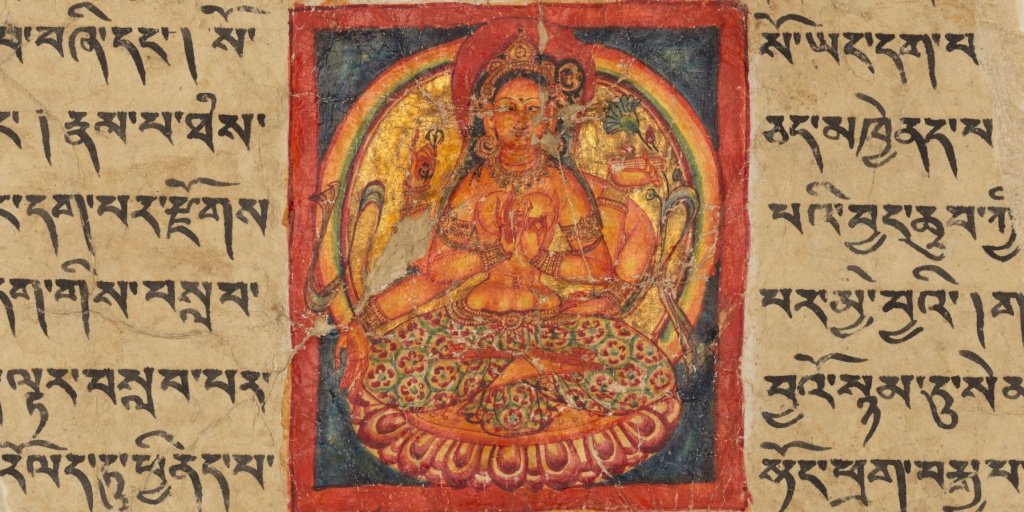

Gonkar Gyatso. No Love Buddha, 2011

The assignment this week in class was to write about the buddhist doctrine of no-self, as described in early buddhist thought. If you want to explore this corner of Buddhism more I highly recommend this book, an insightful reading of early Buddhist philosophy

༶

The prevailing belief during the time of the Buddha was that there exists in every person an Ātman, a word we can translate as the soul, the self, the witness, or the experiencer. This Ātman moves through incarnations, in different bodies with different names, propelled by the actions it takes and the karmic repercussions of them. What was radical about the philosophy revealed by the Buddha was the negation of the existence of this Ātman. Part of his response to how reincarnation can occur without a ‘soul’ is the doctrine of dependent origination. In this view, all phenomena are just a chain of cause and effect; nothing exists independently, everything that exists came into existence as a result of causes, and it will cause other things to happen. All matter and form [rupa] is made of other matter and form and will become still other types of rupa. We are made out of stardust, and to stardust we will return. The 'self' you experience is just a link in an eternal chain of cause and effect, a moment in spacetime, and can only 'exist' due to the existence of the whole rest of the chain.

In his dialogue with King Milinda, the sage Nagasena explains how we can have this seeming experience of existence while denying the existence of a self. There are two main ways he goes about explaining this, through the doctrine of the skandhas, and the concepts of conventional vs ultimate truth. We take the exhaustiveness claim as our base, that every part of a person is represented in physical form and the other 4 skandhas (feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness). He goes category by category showing that while we have experiences through these 5 skandhas, the self is not contained in any single one of them, nor is the aggregation of them together truly a ‘self’. These skandhas are merely the doors of perception through which existence is experienced.

If that is indeed the case, then how is it that we experience such a strong sense of selfhood? Because the ultimate truth, the lack of existence of a self, is a different thing than conventional truth, how we go about labeling and experiencing things as humans. The Buddha would give discourses from both levels of truth, based upon context and the level of realization of his audience. On a conventional level, we experience incarnation as the inhabitation of form and the experience of consciousness, constructed as the ego based “I”, and there is good reason for this! So that we can learn and grow and interact with each other. But on the ultimate level, there is no identifiable entity that is a ‘self’. There is merely a series of causes and effects cascading like a line of dominoes, until the chain is broken when the cessation of craving and attachment is attained.

The experience of consciousness that is me, Maya, writing this paper, exists in a conventional sense. I can tell stories about my past, have dreams about my future, and experience the keyboard under my fingers as I type. None of this is being denied in the doctrine of no-self except for ultimate identification with the concept of ‘I’. On a conventional level, I exist as an independent entity, subject to the laws of karma and rebirth. On an ultimate level I am the formless vast expanse, that which is neither born nor unborn, that which neither exists nor does not exist.

༶

Gonkar Gyatso. Sustainable Happiness, 2012

The Buddha’s first teaching: on suffering

This is a short paper I wrote for buddhist philosophy class on the first teaching given by the Buddha, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta. In this discourse he defines the four noble truths, beginning by explaining the pervasive nature of suffering (‘dukkha’ in the original pali). This paper is p academic and not very positive vibes cuz that’s not what the prompt was about but for those interested here u go :)

To understand the meaning of suffering in Buddhist thought, it's important to explore the original word that we translate it from. It seems as if dukkha is a word that exists in response to all that it is not. It is often discussed in contrast with the word ‘sukkha’, a similar word with an opposing meaning. On a base level sukkha connotes a positive experience, and dukkha a negative one. Sukkha can mean ease, pleasure, comfort, happiness, and well-being. Dukkha appears where these qualities are absent. It has been variously translated as discomfort, unease, unsatisfactoriness, difficulty, and unhappiness. The Buddha spends the first words of his first teaching illuminating all the places that this dukkah arises, bringing his new students face to face with the fundamentally unsatisfactory nature of reality.

The Dhammacakkappavattana sutta begins with the Buddha explaining how dukkah pervades all existence. He describes the 3 different forms of dukkah, tells that there is a way out of this experience, and describes the way. These are the four noble truths. To find a way out of this omnipresent unease, we must first see the depth to which we are trapped by it. It is from this understanding that the Buddha taught the 3 types of suffering we are subject to in conditioned existence.

The type of suffering that is most immediately obvious is dukkha-dukkha, the suffering of suffering. Experiencing it is as easy as getting a papercut or stubbing your toe, it is an unpleasantness that the mind experiences as a result of pain. While the event that caused the pain may come from physical stimuli, dukkah-dukkah refers to the registering of the pain as unpleasant by the mind.

The 2nd kind of suffering is called viparinama-dukkha, or the suffering of change. It arises in response to pleasurable experiences, manifesting in the realization that the pleasure will inevitably end. It is a negative response to the transience of conditioned existence, an emotional sense of loss or craving for pleasure. On a subtle level it could be a dissatisfaction with the pleasurable sensation itself, because the mind knows it will end despite the dopamine rush of its present distraction.

The 3rd kind of suffering is called sankhara-dukkha, or pervasive compounding suffering. Instead of simple aversion to a stimulus perceived as painful, this discomfort is a creation of the ongoing judging mind, which assigns blame and attempts to find escape from experiences of dukkha-dukkha. It is a manifestation of past karmas, and it is always at work generating stories to remove the mind from present experience. It is especially noticeable under stress, manifesting as reflection, projection, anxiety, worry, and depression. It is existential suffering, the suffering of the mind examining the reality of conditioned existence without knowing a way out.

By beginning his first discourse by expounding upon dukkha, the Buddha laid the groundwork for teachings he would give throughout the rest of his life. In understanding dukkha and the varied ways it manifests, we see that the underlying experience of conditioned existence is the absence of feeling good. Sometimes this is experienced more grossly, and sometimes more subtle, but the sensation of wrongness is pervasive and unlimited. According to the Buddha, it is only through accepting this fact and beginning to eradicate the roots of dukkha, that the journey toward liberation can begin.

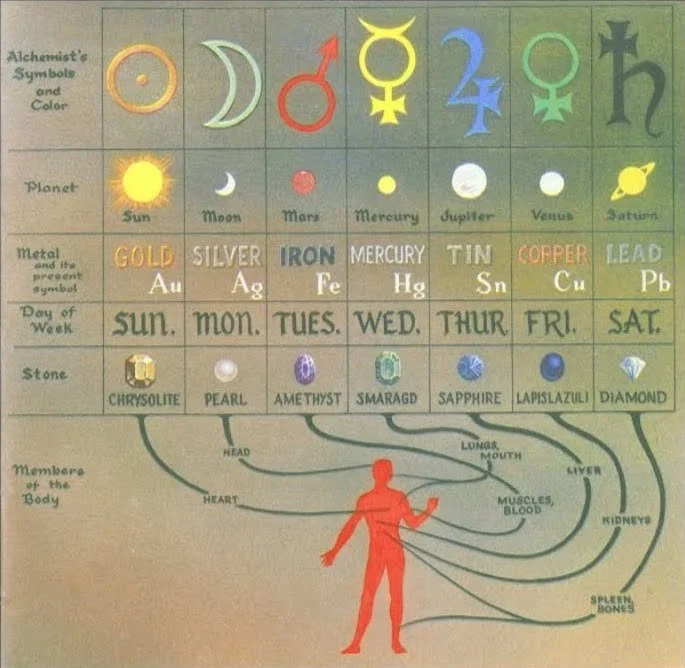

Planetary days Pt.1

Planetary days

7 days of the week

7 planets

named after each everywhere in the world (wikipedia)

get into the vibe

Sun/ father apollo reinholder of the 7 authority and light you raise us from the earth and animate our structures with the great drama of your spotlight

Sunday/ make a statement soak up some rays relax in a sunbeam tell the world who you are rest in the limelight . Wear gold leopard yellows whites sunglasses hats feel good to feel good.

Moon/ mother superior wet pearly dissolver messenger mother divine she qhispers through the wet ice worlds through mists and memories of longing

Moonday/ rest forgive meditate sleep bathe make offerings cry release cocoon. Wear silver white greys pearls opalescent sheer milky

Mars/ the strong the mighty the bravehearted violent uprising of blood and valor that bleeds for the cause and love of the fight

Tuesday/ work up a sweat take the plunge break the seal hit the decks push the limit. wear red workout clothes cat eye sharp enough to kill a man

Mercury/ think quick before the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog twist your tongue twist your words tricksy mr. anything

Wednesday/ think write message edit gamble correct deliberate calculate communicate translate connect compare contrast. Wear whatevers light and quick lululemon running

Jupiter/ The priest of the planets god of the gods one of the all the great benefic jovial joyous jupiter

Thursday/ cant go wrong with a thursday , pray praise god gratitude luck boons and blessings im feeling lucky. Wear whatever you want lapis and amethyst lots of layers and accessories

Venus/ Lady miss thing sexy mama boots love queen enchanting beauty babe

Friday/ Make love not war seduce beautify indulge enjoy the sensual delights sweet music sweet flavors nurture your love. Wear red pink sexy lace date night makeup perfumes and silks and fine jewelry

Saturn/ Cold dry dark grim reaper man in black here to make things hard so you LEARN

Saturday/ do the work, commit, endure, embrace suffering, practice, abstain, fast, honor ancestors. wear black goth motorcycle bad boy blacked out maybach sunglasses